What happens to collections after museums close? Over the next two years the Mapping Museums Lab will be looking at that question in more detail, but even in these early stages of the project we’re beginning to get a sense of some of the outcomes and of the objects’ destinations.

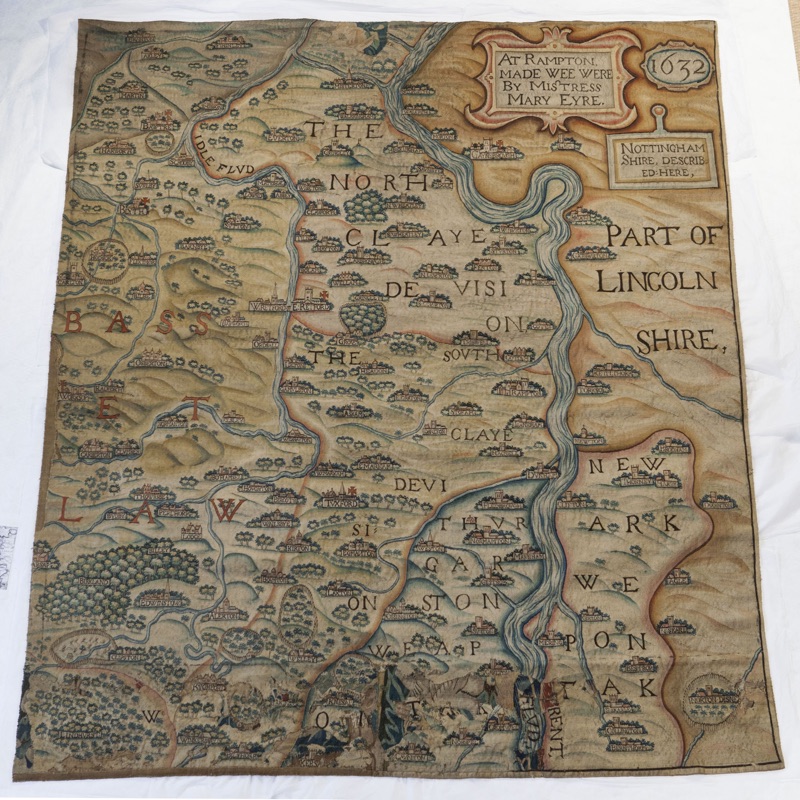

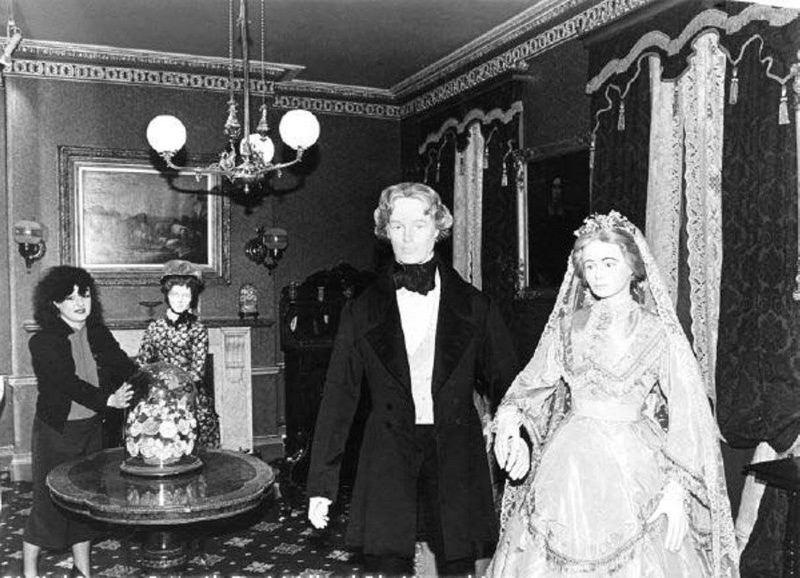

We’re concentrating on museum closure in the UK since 2000 and so far, museums’ governance seems to make a significant difference to where objects end up. The collections from local authority museums are generally returned to or absorbed into the county or city service, and often re-appear in other spaces and exhibitions. For example, the Nottingham City Museums service operated multiple sites including The Museum of Costume and Textiles [1976-2003]. After it closed to the public, the collections were stored onsite, then re-located to the historic house Newstead Abbey, with some items later going on exhibition in various other museums within the service. Among other things, two seventeenth-century tapestry maps of Nottinghamshire, which had been on permanent display at Museum of Costume and Textiles, and were stored following its closure in 2003, were prominently displayed in the “Rebellion” themed gallery at Nottingham Castle when it reopened in 2021.

We found similar trends in other local authority museums that closed. Artefacts from St Peter’s Hungate Church Museum [1933-2000] reappeared in the decorative arts galleries at Norwich Castle and in the period rooms at Norwich Museum at Brideswell, museums operated by the same local authority. The Manor House Museum [1993-2006] in Bury St Edmunds had a collection of fine art, costume, and perhaps most notably clocks, which went to their sister institution Moyse Hall. The costume and art are incorporated into social history displays as and when they are required, while the clocks have a permanent space.

In a few instances the local authority mothballs a museum leaving everything in situ. In some cases, this allows for some continuing use. The Museum of Lancashire [1972-2016] in Preston has been closed for several years, but the galleries with recreated spaces – a Victorian classroom and street scene, and a World War 1 trench – and all the associated objects remain untouched and are regularly used for education sessions. When I first spoke to staff in November 2023, hundreds of schoolchildren had been through the otherwise closed museum in the previous weeks. Moray Council took a more drastic approach when it shut the Falconer Museum in Forres [1871-2019]. The collections in the store and displays in the public galleries remain as they were left when the staff left on their last day, and the only people who have access are the conservation officers responsible for checking the building and collections.

So far, we have not found any independent museums that mothball their collections. In some cases, the trust or organisation that ran the independent museum still exists and they retain ownership of the artefacts, loaning them out to other organisations. For instance, the instruments from the Asian Music Circuit Museum [1998-2014] are on long-term loan to the Music department at York University, although it is not clear whether they will ever be returned. In other cases, the collections are transferred in their entirety to another museum. When the independent Bexhill Costume Museum [1972-2004] faced closure early in the millennium, the director negotiated a complete transfer of collections to Bexhill Museum, which was accordingly redeveloped with support from the local authority, re-opening in 2007. Likewise, the contents of Earby Lead Mining Museum [1971-2015] went wholesale to the nearby Dales Countryside Museum, which was local authority run.

The collections from the private museums that we have so far researched are frequently sold, often at auction. Occasionally we know who bought the objects. The Cars of the Stars Museum in Keswick, which included vehicles featured in James Bond films, was purchased in its entirety by Michael Dezer who relocated the collection to his museum in Miami, Florida. When the company museum at the entrance to the Minton factory closed [1950?-2002], the Potteries Museum in Hanley bought a 4ft tall ceramic peacock that had stood at the entrance. More usually, these objects disappear into the anonymity of the private sphere.

Researching closure is a slow and painstaking task and it will be several months more before we begin to have a more rounded picture of what happens to museum collections. It may be that our observations will be revised in the process. They will certainly be developed and refined. Over the next few months, we will be exploring numerous topics related to museum closure: which objects get scrapped, the emotional aspects of closure, and the possible corelations between social deprivation and dispersed collections. Do subscribe to our blogs on this new website for updates on our progress.

Fiona Candlin

Update: this blog was updated on 12 March 2024 to correct the status of Bexhill Museum.

3 replies on “The afterlife of museum collections”

I talked to a dealer at a flea market when he had a wide variety of early medical electric shock machines.

He had cleared the flat of the late collector from an affluent area of London and sold most items over eBay and bought the cheaper stuff to the flea market to clear it more quickly. Sad that an excellent collection was broken up and dispersed.

In another case a geology department collection of rocks and minerals in bespoke wooden storage chests of drawers in a college was skipped as there was no time or inclination to find a suitable home.

Sadly artifacts can get lost even when museums close and the items are dispersed amongst the councils other museum sites. It may be that they have lost their identification tags? We have been chasing the fate of the sword belonging to the Earl of Glencairn and this seems to have been its fate.

The distribution of the Yorkshire Dales Lead Mining Museum at Earby was a little more complex although the bulk went to The Dales Countryside Museum other items were taken by other public collections. The DCM is run by the National Park, which is similar to local authority but I think the only accredited museum governed by a National Park