We began the Mapping Museum research by investigating the numerous surveys and reviews of UK museums that have been compiled since the 1960s. Our intention was to use that material as the basis for our own dataset, but it gradually became clear that the various government and charitable bodies who had conducted the surveys or collated the lists did not always include or exclude the same venues. They all had subtly different ideas of what a museum was.

Clearly, the motivations for surveying museums vary depending upon the remit of the association or body that is conducting the survey. If a review is focused on state support then there is little reason in spending time and money investigating independent museums, art galleries without collections, and examining regimental collections would be pointless if the survey is meant to look at the role of university museums. It is not that the surveys have been inaccurate, or that we should advocate for a more perfect overview, rather that they are designed for particular purposes within specific contexts. Even so, the selectivity of a survey does matter, especially when they concern museums in general. In adopting one set of terms over another, or in deciding that a particular category of venues do or do not fall within their purview, surveys diverge in how they constitute museums. They have each understood museums to be slightly different entities, and this has an impact on how they portray the sector as a whole.

In this and the next two posts I will consider some of the types of venues that have been included or excluded from surveys, and as they are the main focus of our study, I will begin with independent museums.

Independent museums: In or Out?

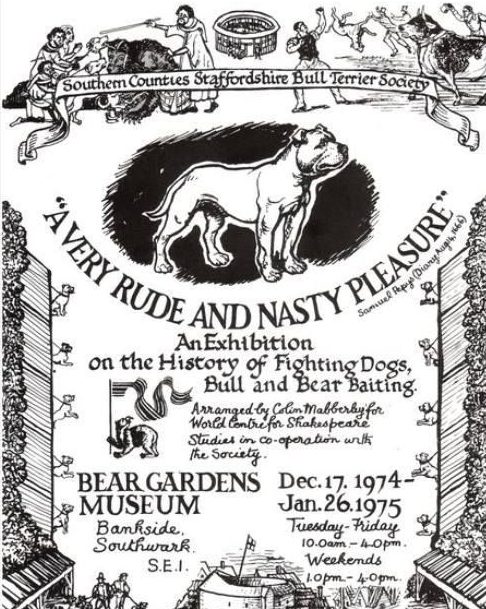

In 1963, the Standing Commission stressed that they had considered ‘museums run by every sort of authority’. They listed local authority museums, those run by the Ministry of Public Buildings and works (which later became Historic Buildings Commission, then English Heritage), military, school and university museums and finally ‘privately-run museums’ of which a few belong to commercial firms, some to local learned societies, and almost all the rest …. are administered by trusts’. At this stage, who ran the museums, under what governance, and with what degree of professionalism, was less important than the fact they were a museum, and what constituted a museum was not raised as a question. Surveys conducted in the 1970s and 1980s were similarly inclusive but that situation had changed by the 1990s.

The shift in approach was motivated by an increasing emphasis on professionalization and specifically accreditation. In 1971 the Museums Association proposed a voluntary accreditation scheme, which would set basic standards in the sector. In order to be accredited, museums had to comply with the association’s benchmarks and with their definition of a museum. Responding to the plan, which was presented at the Museums Association Annual General Meeting, one speaker observed that many small independent museums would find it difficult to meet the first essential minimum requirement, namely, that they had sufficient income to ‘carry out and develop the work of the museum to satisfactory professional standards’. More than that, the accreditation process introduced a definition of a museum for the first time, and as the speaker also commented, it referred to museums as institutions, which the small independent venues were not.

Initially accreditation was voluntary and was run in a relatively ad-hoc way, but in 1984 it was taken over by the Museums Libraries Archives Council and became more closely connected to funding. Museums had to be accredited in order to qualify for public support and so membership of the scheme became increasingly ubiquitous. It also began to be used as the basis for surveys and lists. DOMUS, which was the most comprehensive survey of museums in the UK, only included accredited institutions and omitted an estimated 700 non-accredited museums. At one point the DOMUS team did consider the possibility of including non-accredited museums and of generating a more comprehensive view of the sector but it came to nothing, not least because the survey data was gathered in tandem with the annual accreditation returns, and so there was no process for collecting information on these additional museums.

The situation, wherein small independent museums did not meet the requisite standards and therefore were largely absent from official data, was exacerbated when the definition of museums changed in 1998. The new definition added a legal stipulation, which was that museums had to keep their collections ‘in trust for society’. Again, this concerned the contract between museums and the public because establishing museums as trusts helps ensure that collections are not sold or used for private gain, which is especially important when funding is involved. The result was that from this point onwards any museums that were run on an ad-hoc basis with little official governance, were constituted as commercial enterprises, or were owned by families, individuals, or businesses, ceased to appear in official data. Likewise, museums that did meet the terms set by the Museums Association definition, but had decided not to seek accreditation fell off the official lists.

The Museums Association definition works well as an aspirational target or a guide for professional practice, but it does not describe museums in the world at large. Similarly, accreditation is a useful means of ensuring some accountability with respect to public funding, as is the stipulation that museums should have particular modes of governance. National funding bodies do need to keep track of the museums that have been accredited and are eligible for state support. Nonetheless, using accreditation as a mechanism for collecting information about museums has resulted in a skewed view of the sector. Surveys are structured in such a way that they can only encompass museums that have achieved a particular level of professionalization.

To draw an analogy, imagine that a professional association of musicians declared that music needed to be made within a certain legal context and to be of a certain standard in order for it to count as such. The outputs of community choirs, folk musicians, pub bands, would no longer qualify as music unless they had established themselves as trusts. Yet, in the case of museums, such a definition has been widely adopted and implemented. The museum equivalents of pub bands do not appear in official surveys. In consequence, they do not figure in accounts of the sector or to a large extent in academic histories of museums. It is, as if museums only operate within the sphere of official culture.

Interestingly, some unaccredited museums appear in the Museum Association Yearbooks and more recently on their online Find-a-Museum Service. Although the Museums Association has been one of the main drivers in setting standards and establishing definitions of museums, they are also reliant on membership fees for income. Anyone who pays to join can submit their details, and the Association do not police entries according to their own criteria, since that would result in a drop in revenue. There is some irony in this situation. The Museums Association’s work on establishing definitions has resulted in smaller museums being excluded from official consideration but nonetheless its publications and website are among the few places where non-accredited museums are listed. The Mapping Museums team has used and is greatly extending that data on unaccredited museums, and will be publishing lists of museums in general, not just those that meet professional criteria.

© Fiona Candlin November 2017