What does the Mapping Museums research assistant do all day? I sometimes wonder where all the time goes. Although the vast majority of the four thousand-odd museums listed in the database were added before I really began work on the project, I’ve added well over a hundred new museums and made corrections to the entries for hundreds more. But how do we find out about museums that were not already in the database, and where do all the amendments come from? Here I offer a peek into a ‘typical’ week.

Monday

A friend of the project reports on Twitter a possible new museum she’s spotted while on a bike ride. It turns out that it is not new, but the small private museum has slipped under the Mapping Museums radar, so I add it to the database. Another contact has suggested we check a directory of railway preservation sites to make sure we haven’t missed any railway museums during our searches. I order it from the British Library for my next visit.

Tuesday

I have Google news alerts set up in the hope of spotting museums closing and opening, and I open my email this morning to find an alert for a new museum. All too often these alerts don’t produce anything useful, but on this occasion they have. A new private museum dedicated to the footballer Duncan Edwards has opened above a shop in Dudley, in the West Midlands, so I make a note to add it to the database.

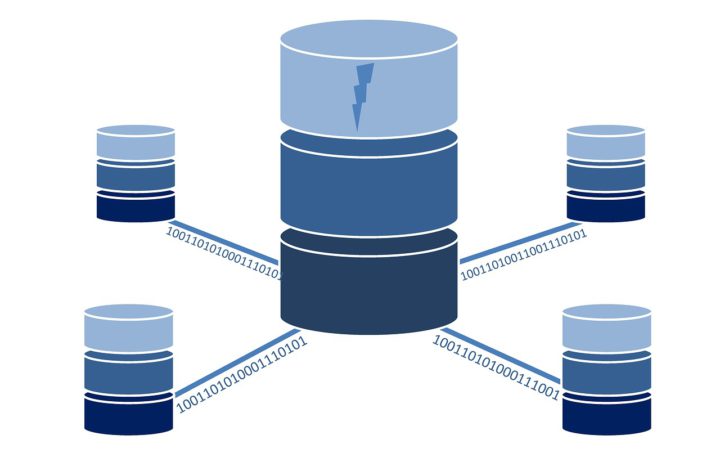

The Mapping Museums database is constantly being updated. When we receive new information for museums currently open, we update our records accordingly. Today I find that a curator has supplied updated details for their museum using the form for editing data, and process the update so that the details are added to the database.

Wednesday

At the British Library for my own PhD research, I also look at the railway preservation directory. At first sight it looks somewhat daunting, as it lists hundreds of railway preservation sites in Britain opened from the 1950s onwards, classified into thirteen types. Each one of these will potentially need to be checked against the database to see whether museums need to be added. I copy the pages I need for processing later.

Looking through copies of Museums Journal I see mention of another museum that I’m not familiar with. It’s in the database, but the news item gives extra information about the museum’s governance that we didn’t have, so I make a note for later.

Sometimes we need to contact museums directly to confirm information, and recently I have been trying to get hold of the administrator of a small military museum in Scotland (the museum came to our attention as part of a list supplied by a liaison officer for regimental museums). The administrator is only on site occasionally, and so far I have missed him each time I’ve called. I miss a call while sitting in the library’s reading room, and when I return it later I have just missed him, but his colleague supplies his email address. By email he confirms the nature of the collection, but does not know when the museum was first opened – he has been in the post for less than two years. One thing I’ve discovered doing this research is that it is quite common for the opening date of museum not to be known by those who run it. A museum’s foundation date is often tacit knowledge, which can easily be lost as staff change. The database currently contains almost five hundred museums for which we do not have a certain opening date, and we record them as date ranges instead based on the best information available.

Thursday

I resume work on a list of museums that another contact has provided us with. They are all in North East England. Not all of them qualify as museums in the way that the project defines them but many do, and for whatever reason some have been overlooked. Small private museums are easily missed, and it would not be possible for the project to have compiled as comprehensive a list as it has without the benefit of local knowledge. One example is the Ferryman’s Hut Museum in Alnmouth, which I add to the database.

Friday

The opening date of a museum is proving elusive. My enquiry to the owners remains unanswered, so I resume searching online. Eventually I track it down in the Gloucestershire volumes of the Victoria County History, an incredibly valuable local history resource.

It’s fortunate that that museum was recorded, but what do you do when a museum has long closed and there are no references to be found online, no matter how hard you search? Well, you might descend the archive.org rabbit hole. As anyone who has followed references in Wikipedia may have noticed, website links stop working all the time – a phenomenon colloquially known as ‘link rot’. The Wayback Machine preserves websites for posterity, keeping copies of those still online as well as many that have long since vanished. In this case we knew that the museum had closed thanks to an estate agent’s website, but when did it open? The website for the tower in the Scottish Borders had fortunately been captured by the wayback machine, and while there was no definitive information about the museum, there was enough to allow a range of dates for the museum’s opening to be recorded.

It’s the end of another week of data collection and checking. That list of hundreds of railway preservation sites will have to wait until another time …

Mark Liebenrood