The National Fencing Museum was established in 2002 in by Malcolm Fare, a fencer and fencing historian. It includes displays of fencing equipment, paintings, prints, books, and all kinds of ephemera.

Image via the museum.

The National Fencing Museum was established in 2002 in by Malcolm Fare, a fencer and fencing historian. It includes displays of fencing equipment, paintings, prints, books, and all kinds of ephemera.

Image via the museum.

Patrick Cook, the founder and owner of the Bakelite Museum, started collecting plastic when he was an art student in London. Among other things, he used his collection to hold a series of Bakelite picnics, where the crowd ate food off Bakelite plates, drank tea from Bakelite cups, and listened to music played on Bakelite instruments. In 1983, Cook opened a Bakelite Museum, and in 1994 he moved the collection to its current location in the village of Williton in Somerset, opening to the public the following year. The museum is about to move again, and before it does so, we wanted to film the museum in its current incarnation.

The Mapping Museums project was motivated, in part, by the lack of documentation of small independent museums. Our research indicates that just over 2,500 independent museums have been open in the UK at some point since 1960 (This figure is higher if we include museums managed by the National Trust and other national organisations). These new independent museums focus on diverse subjects – lead mining, Methodism, local history, and Bakelite, and in doing so they make an important contribution to the cultural life of their local areas, and collectively, that of the nation. However, these small independent museums often run on a limited income, which means that they do not have the resources to document their holdings, publish catalogues of their exhibitions, or to keep an archive. Thus, if a museum moves premises, or closes, they may leave little trace behind.

The Mapping Museums project aims at documenting all the museums that have been open in the UK between 1960 and 2020. So far, the research has focused on identifying museums and on providing an overview of how the independent museum sector has emerged and developed. As our work continues, however, we will be looking at individual museums in more detail. This short film, which was made in collaboration with the Derek Jarman Lab, forms part of that enquiry.

Copyright: Fiona Candlin 2018

Hopewell Colliery Museum is in the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire. Mining is an ancient tradition in the forest and those born there can exercise their rights to mine coal, iron ore, ochre and stone. The museum includes a working mine, through which visitors can take a guided tour.

Image via the museum.

The Buxton Transport Museum was relatively short-lived, open for only three years. It was established in 1980 by Peter Clark, a vintage car enthusiast. The site is now occupied by Buxton Mineral Water company.

Images and information via Badge Collectors Circle and Derbyshire Through Time by Margaret Buxton on Google Books.

The Douglas Museum was the brainchild of Randolph Osborne Douglas, who created it in his home in Castleton, Derbyshire with his wife Hetty. Douglas was a silversmith, locksmith, and amateur escapologist with the stage name of The Great Randini, inspired by his childhood hero Houdini. His collection included miniature houses, locks, models of the world’s largest diamonds, a variety of Houdini ephemera, and many other curios.

Douglas opened his museum in 1926. After he died in 1956, Hetty continued to run the museum until her death in 1978. The collection was transferred to Buxton Museum and parts of it are now on show in the small museum at Castleton Visitor Centre.

Images by Mark Liebenrood.

An area that initially passed us by on the Mapping Museums project was the prevalence of sports museums. While we recorded the more obvious, high-profile venues such as the MCC Museum and National Football Museum, we were unaware of the increasing numbers of club museums. This growth has occurred across team sports, such as rugby and cricket, but is particularly evident at football clubs. The development has not been prompted by clubs’ newfound interest in preserving their heritage – after all, there have always been trophy rooms to display cups and medals – but in opening up those collections to their supporters and the wider public. This seems to have begun with the introduction of stadium tours in the late 1990s/early 2000s, as part of an effort by clubs to market themselves as venues for more than a couple of 90 minutes matches each week. As such initiatives have taken off, club museums have increasingly become attractions in their own right. Indeed, interest in club history can be gauged in part by the success of exhibitions hosted in local museums, of which there have been innumerable in recent years. Exhibitions like that at the Dorman Museum in 2012, which celebrated the 25th anniversary of the ‘rebirth’ of Middlesbrough Football Club, are testament to the depth of local attachment to their teams; a feeling that clubs may well seek to tap into to develop a more expansive museum offer moving forwards.

Further, there is now greater awareness of the importance of this history across the museums sector, with the recent launch of Sporting Heritage, a project in some ways similar to our work, which maps various sporting collections held in museums throughout the UK. Hopefully, their work will act as a focal point to help support the growth and development of these emerging sporting attractions.

Below we have compiled our own list of (mainly Premier League) football clubs that have museums – either their own or supporter run – and those with plans to develop them. If we have missed any club museums, however small, please do let us know via twitter @museumsmapping or in the comments below!

Arsenal FC

Arsenal Museum

Brighton and Hove Albion FC

Club museum opened in 2014

Burnley FC

Supporter run online museum

Celtic FC

Museum as part of stadium tour

Charlton Athletic FC

Museum established in 2014

Chelsea FC

Stadium Tour and Museum

Crystal Palace FC

Plans for a museum in forthcoming stadium redevelopment. Some club artefacts on display in the Crystal Palace Museum.

Hull City AFC

Online museum run by supporters

Leeds United FC

Museum is planned

Manchester City FC

Small museum exhibition included in Stadium Tour

Manchester United FC

Stadium Tour and Museum

Liverpool FC

The Liverpool FC Story – interactive museum

Newcastle United FC

Small museum exhibition included in Stadium Tour. Recent record-breaking exhibition of club history at the City’s Discovery Museum.

Sheffield United FC

Memorabilia of world’s oldest football club on display in ‘Legends of the Lane’ Museum

Tottenham Hotspur FC

Club stadium currently under redevelopment and upon re-opening will include a museum space

Watford FC

No known museum but memorabilia on display in Watford Museum

West Ham United FC

Club did have a museum that was opened in 2002, but current status unknown following recent stadium move

Wolverhampton Wanderers FC

Museum established in 2014

Copyright Jamie Larkin, January 2018

On Friday 26th January, the Mapping Museums project reached the end of its first phase, and for us, it felt like a momentous date. For the last fifteen months Dr Jamie Larkin and I have been compiling a huge dataset of all the museums that have been or were open at any point between 1960 and now. That information has now been finalised and handed over to the computer science researcher to be uploaded. In the coming weeks, we will be able to start analysing our material and generating findings about the past sixty years of museum practice in the UK.

The dataset of museums synthesises information from a wide variety of different sources. We started with DOMUS (The Digest of Museum Statistics), which was a huge survey of museums conducted in the mid 1990s and with the 1963 Standing Committee Review of Provincial Museums. These captured a large number of museums that were open in the mid to late twentieth century, but have since closed. We then added current records and information from the Arts Council England (ACE) accreditation scheme, and from the national records gathered by from both Museum Galleries Scotland (MGS), and the Welsh Museums Libraries Archives Division (MALD) and the Northern Ireland Museums Council (NIMC), since these lists both include non-accredited venues museums. The Association of Independent Museums (AIM) gave us a list of the museums that have been members their membership records and we also managed to find the results of a very old survey that they had conducted in the 1980s in the University of Leicester Special Collections library. This was research gold for it identified very small museums that are extremely difficult to trace once they have closed.

We included around half of the historic houses that are listed in the Historic Houses Association guidebook, and a number of properties that are managed by English Heritage, Historic Environment Scotland, or CADW. Deciding which venues reasonably constituted museums was a difficult process and one that we did in consultation with senior managers and curators of those associations, colleagues from the Museums Development Network and with the ACE accreditation team, although the final decisions were our own.

In the course of researching my last book Micromuseology: an analysis of independent museums, I had compiled a list of very small idiosyncratic museums, and these were added into our rapidly growing list, as were a surprisingly long list of museums that were listed online but not in any of our other sources. We then checked our dataset against the Museums Association ‘Find A Museum Service’ and against two huge gazetteers The Directory of Museums and Living Displays and The Cambridge Guide to the Museums of Britain and Ireland edited by Kenneth Hudson and Ann Nicholls in 1985 and 1987 respectively. Finally, we also consulted the Museums Association Yearbook at five yearly intervals from 1960 until 1980 and also a variety of publications that listed historic houses that were open to the public. In all cases, any venues that we had previously missed were added.

Having established a long list of museums we needed to ensure that we had a correct address, and the opening and closing dates for each venue. We also wanted to establish its governance, whether it was national, local authority, university, or independent, and if the later, if it was managed by a charitable trust or by a private group. Finding this information necessitated months of emailing and telephone calls, and we often ended up speaking to the children of people who had founded museums, or to members of local history associations in the relevant area. Even so, the process of compiling our dataset was not yet finished for we also needed to classify each museum by subject matter. In order to do this we devised our own classification system and considered each venue on an individual basis. It is little wonder that major museum surveys are infrequently undertaken.

The next phase of the research is analysing the data, so watch this space for updates. The first findings on museum opening and closure will be presented at ‘The Future of Museums in a Time of Austerity’ symposia at Birkbeck on February 24th 2018. We will also be tweeting about interesting aspects of our analysis, so don’t forget to follow us @museumsmapping on twitter.

Copyright Fiona Candlin January 2018.

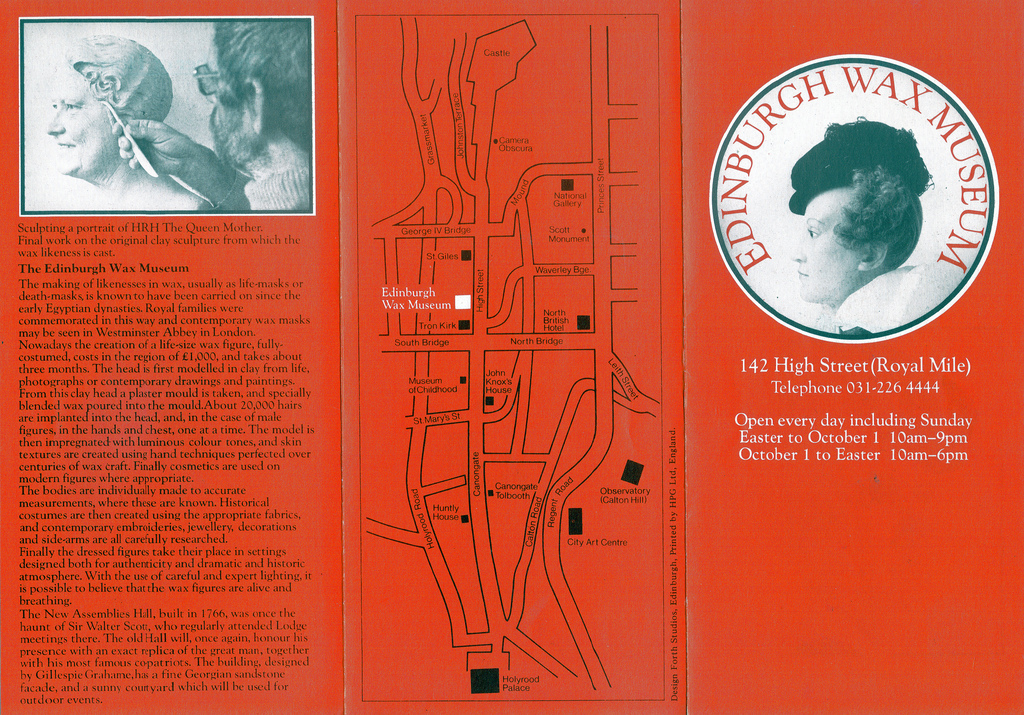

Edinburgh Wax Museum opened in 1976 and was soon attracting more than 230,000 visitors a year. Displays included Scottish historical figures, fictional characters, and, as you might expect, a chamber of horrors. The museum was curated by Charles Cameron, a professional magician, who also performed as Count Dracula in night-time shows in the Castle Dracula Theatre on the top floor.

Despite its popularity the owners decided to sell the premises for office development and the museum closed in 1989, joining the ranks of lost wax museums. The premises were up for sale again in 2008, but it seems nothing came of plans to reopen the museum.

Images via Flickr.

The Spalding Bird Museum was owned by the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society and run by Ashley K. Maples and taxidermist Ben Waltham. It contained 840 specimens of British birds and many other specimens, in 160 display cases. Maples died in 1950 and a lack of funds forced the Society to sell the premises in 1953, when a small part of the collection was moved to Ayscoughee Hall and much of it loaned to Leicester Museum. The Hall closed for refurbishment in 2003, when the whole bird collection was transferred to Leicester Museums Service.

Images via South Holland Life (PDF)

Museum closures are a matter for concern. The austerity measures introduced under the current government have resulted in local authorities reducing funding for museums and some have been forced to close. In this workshop we examine the landscape of closure within the UK. How do rates of closure compare with previous decades and also with rates of new museums opening? What’s lost when a museum closes? And is closure always a problem? Is it really necessary to have so many museums keeping their collections for posterity?

Chair: Professor Fiona Candlin, Director Mapping Museums research team, Birkbeck

Speakers:

Dr Jamie Larkin, Mapping Museums research team, Birkbeck

Alistair Brown, Policy officer, Museums Association

Emma Chaplin, Museums consultant

Jon Finch, Re-Imagining The Harris – Project Leader

Museum closure is often an emotive subject. While the sector can point to recent closures and their causes, there is little understanding of how such trends play out over the longer term. This talk will present preliminary findings of the Mapping Museums project concerning museum closure between 1960-2018. It reflects on the methods used to trace information on closed museums and the conceptual problems encountered during the data collection. The talk then examines long-term closure trends through a number of key characteristics (e.g. location; subject matter; governance) and considers the implications that these findings may have for the sector at large.

Dr Jamie Larkin

The Museums Association has been monitoring museum closures over the last decade. How do we define closure? How have trends around closure changed? What has the impact of austerity been? And does the issue of closure obscure other major trends in the sector at present? Alistair will examine how closure figures have been gathered, interpreted and used as an advocacy tool on behalf of the museums sector.

Alistair Brown

During 2016 Emma and her colleague, Heather Lomas, carried out research for Arts Council England and the Museums Association about how museums deal with the reality of closing a museum. She will explore what happens when closure decisions are made, the challenges that are presented and the implications this has for governing bodies, staff, volunteers, the sector and the communities that museums have served.

Emma Chaplin

Local government has been and remains the largest investor in local government across the UK. However the ongoing fall out from the financial crash of 2008, and the austerity measure put in place by national government, has led to a massive decline in the funds available to Councils. This has led to authorities to reviewing and drastically reducing their investment in a range of services, including museums. Therefore there has been a significant reduction of museum services in many places, and in some instances closure. However in certain localities local authority supported museums are thriving, sometimes with increased investment. Why do some Councils value their museums so highly, when others seem so ready to do without theirs? Jon will use his extensive experience of working with museums across the country to explore the reasons behind Councils’ decisions to close museums. He will use the recent closure of five museums by Lancashire County Council as a case study to consider the impact of such decisions and how local authorities might be helped to make informed decisions in the future.

Jon Finch