Photo: Andi Sapey

Is it closed?

When is a museum closed? It seems like there would be a fairly obvious answer to this question, which would be a matter of public record and quite easy to track down. But working on this project, Museum Closure in the UK 2000–2025, we have not always found this to be the case.

Back in August 2024, Maria Golovteeva and I were drafted in to undertake research on a list of museums where information about their closure (or even if they had closed) had been especially hard to track down. Over the last seven months, we’ve used every research skill at our disposal to try and find out what happened to the museums on this list.

For some, like the Abriachan Museum (aka the Croft Museum) in the Scottish Highlands or the Baird Museum of TV (aka the Radio Rentals Museum) in Swindon, we discovered that the museum had closed prior to 2000 and so was outside of the scope of this project.

And for others, like the Brookeborough Vintage Cycles Museum in Northern Ireland or the Naseby Battle and Farm Museum in Northamptonshire, we finally tracked down information about the closure and the dispersal of those museums’ collections. Or, as with Collectors World in Norfolk (fig.1), we had to draw inferences about the reasons for closure from a range of sources.

But we also came across other museums that complicated our ideas around closure.

These are museums, like Haulfre Stables in Llangoed in Wales, where it is not at all clear whether the museum has closed or not. To some people I spoke to, Haulfre Stables was definitely still open because the collection is still in situ. But there are no public opening hours and it was not clear how someone would actually go about arranging to view the collection. So, in this case, we made the call that Haulfre Stables had in fact closed in 2012–13 when local authority funding cuts meant that responsibility was devolved to volunteers and the site could no longer open regularly. So, despite the collection still being in situ and potentially being open if someone really wanted to see it, we are labelling this as a closed museum.

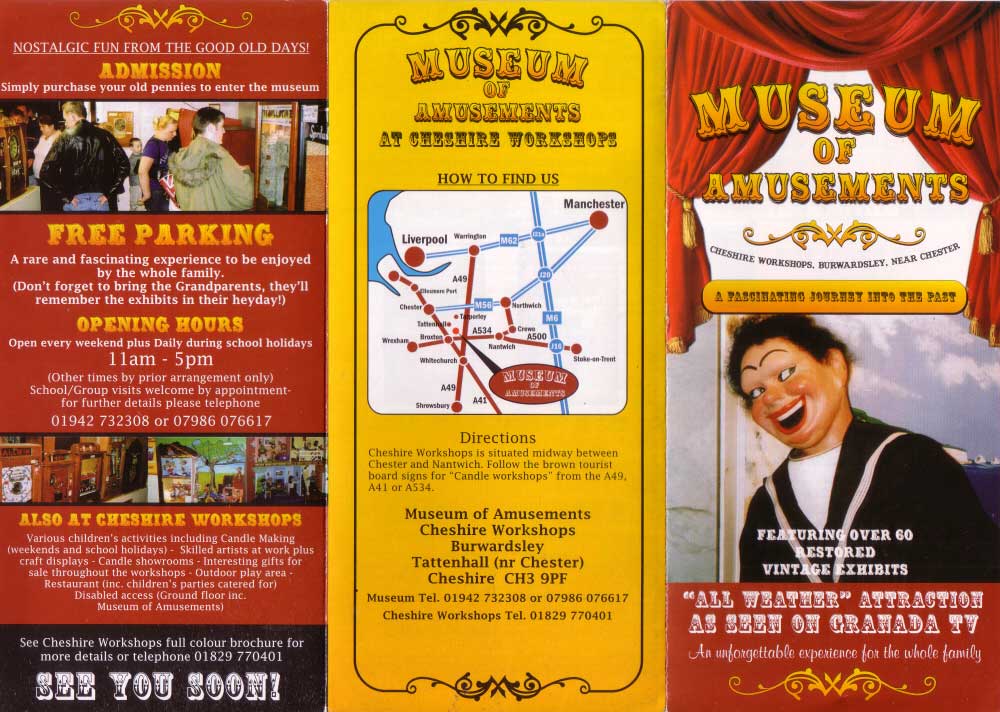

Another example are penny arcade museums where the collection is owned by an individual who may move it to different locations. With one such museum, The Olde Tyme Penny Arcade or Museum of Amusements (fig.2) that had been based at Cheshire Workshops in the 2000s, the owner still retained his collection and it was now just based at other locations. So is this a closed museum, or is it just a relocation? As the newer sites had less of a public presence as a ‘museum’ and the collection was also more dispersed amongst different sites, we again made the call that this was a closed museum, although perhaps it could be argued that it isn’t closed at all.

Sometimes we found that sections of a museum closed but other parts remained, as with Fort Perch Rock Museum on the Wirral where the building had to close for some years because of a water problem. Because of this, part of the collection, the Marine Radio Museum, closed and was removed and dispersed to other museums and collections by the Marine Radio Museum Society, but other collections focused on warplane wrecks, a local submarine loss, and the Titanic remain and are intended to reopen soon. So rather than saying that Fort Perch Rock Museum is permanently closed, it might instead be more accurate to say that the Marine Radio Museum at Fort Perch Rock has closed.

At other times, the process of closure and collection removal appeared to be drawn out and exact dates were harder to pin down. With the Doughty Museum in Grimsby, which was later renamed the Welholme Galleries and then Welholme Galleries Community Museum, the public-facing aspect of the museum seemed to end around 2004, but a freedom of information response from the council stated that the building was used as a museum store until 2009.

And then there has been the occasional museum on our list where we found that it never opened in the first place, as with Challenge at Aldershot (Military & Aerospace Museums), which was intended to open in 1995 on the army base at Aldershot but because of local authority cuts, amongst other reasons, never actually opened. So the museum can’t be said to have closed because it never actually opened.

These are just some examples of museums that have complicated our ideas around closure with it not always being as clear as one might expect about whether a museum is closed.

Helena Bonett

March 2025