The Mapping Museums Lab has just published an article in the Journal of Open Humanities Data about our project on museum closure. If you are interested in finding out more about how we collected and managed the data, the article is open access and free for everyone to read: A Dataset of Collections Dispersal Following Museum Closures in the UK During 2000–2025.

Category: Museum Closure in the UK

The new Mapping Museums report is now out and available online.

After more than two years of concentrated work we have collected data on all the museums that closed in the UK after 2000, why they closed and what happens to their collections.

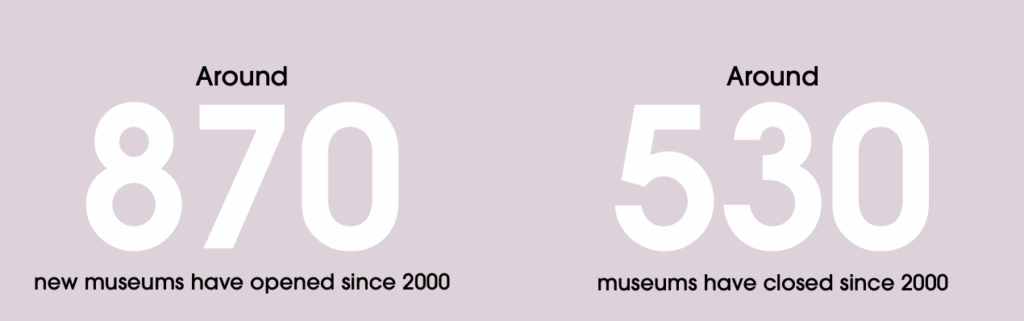

The headline findings are straightforward: the sector has expanded in size since 2000, and when museums did close, their collections were commonly transferred to other museums. That picture becomes rather more complex when we look at which museums closed and opened, and at all the other outcomes of collections disposal.

To find out more read the report (bit.ly/4iAnp7Z)

Or use our new web application: (mappingmuseums.shinyapps.io/mappingmuseums)

Sixteen museums have closed since January 2024. In this blog we report on those closures and look at why they have happened.

Some of the closures were due to local authority budget cuts. These affected Llancaiach Fawr Living History Museum in Treharris, as the council sought to save £45 million over the next two years. In Hampshire, Westbury Manor Museum was running at a deficit and seen as financially unviable by Hampshire Cultural Trust who were managing it. The Trust in turn had had its budget cut by £600,000, almost a quarter of the total, by Hampshire County Council.

A similar situation resulted in the closure of Bursledon Windmill, also run by Hampshire Cultural Trust. Eastleigh Borough Council had been contributing funding for the Windmill, but they terminated the agreement with the Cultural Trust in February 2023.

In Scotland, Alyth Museum was closed after a package of cuts planned by its managing trust, Culture Perth & Kinross, as it reorganised its operations after a 12% cut in its council funding spread over three years.

Independent museums often receive external funding, and cuts resulted in the closure of the independent open-air museum at Auchindrain, the sole example of a Highland farm township. In this case, Historic Environment Scotland ended their funding after providing around 90% of the museum’s costs for three years. The trustees stated that the costs of running the venue, which had been offset by the HES funding, far outweighed the income that they were able to generate. Although the museum is now closed to visitors and, according to the trustees, ‘unlikely to reopen in its present form’, whether the museum will close permanently remains unclear.1

Other independent museums have faced difficulties with costs. Announcing the decision to close Wirksworth Heritage Centre in Derbyshire, its trustees cited ‘the current economic climate, increased running costs and poor trading conditions’. Meanwhile, for Durham Museum the condition of the building was the deciding factor. It needed expensive repairs, including a new roof. The prospect of these costs meant that the Bow Trust who ran the museum felt unable to continue. The Fairground Heritage Trust also found costs to be prohibitive and in late 2024 closed Dingles Fairground Museum in Devon.

A few private museums, all in Cornwall, also closed for financial reasons. The Flambards attraction in Helston stated that rising costs and a steady decline in visitor numbers had made the park’s operation and further investment unsustainable. The Cornish Heritage Museum was housed at the theme park Dairyland in Newquay, which had been running a deficit since the pandemic and decided to call it a day in 2024. The Charlestown Shipwreck & Heritage Centre, based not far away in St Austell, was one of Tim Smit’s businesses and Smit, the founder of the Eden Project, stated that he had decided to close the museum as part of a process of ‘consolidation’, saying that it raised insufficient revenue.

Other museums closed for reasons related to their premises. The independent Welsh Museum of Fire were concerned that their current premises, an industrial unit, were likely to be unsuitable for younger visitors and they are looking for alternative accommodation. The RAF Signals Museum closed in 2024 as RAF Henlow, where the museum was based, was to be closed down. Redevelopments at University College London in preparation for its bicentenary have prompted the relocation of the university’s art museum this year to smaller premises on the site. Although the museum’s new location will include storage and a study space, it will have no exhibition space. As one of our project’s criteria for a museum is that it should have some of its collection on display, we now consider this museum closed too.

Lastly, we know from looking back at closures since 2000 that private museums commonly close because their owners wish to retire. This was the case at Marshland Maritime Museum near Kings Lynn, and the Moretonhampstead Motor Museum, both closed in 2024.

We’d like to thank staff at the various Museums Development Networks, Museums and Galleries Scotland, the Welsh Government, and the Northern Ireland Museums Council, all of whom have helped us to keep our data up to date.

We will continue to monitor closures for the remainder of 2025 so if you become aware of any museums closing, do let us know.

Mark Liebenrood

Images: Elliot Brown on Flickr; Nilfanion on Wikimedia; Steve Knight on Flickr; all Creative Commons.

- Since this blog was published, Auchindrain has announced that it will reopen on 20th July 2025 [updated 30 June 2025] ↩︎

Is it closed?

Photo: Andi Sapey

Is it closed?

When is a museum closed? It seems like there would be a fairly obvious answer to this question, which would be a matter of public record and quite easy to track down. But working on this project, Museum Closure in the UK 2000–2025, we have not always found this to be the case.

Back in August 2024, Maria Golovteeva and I were drafted in to undertake research on a list of museums where information about their closure (or even if they had closed) had been especially hard to track down. Over the last seven months, we’ve used every research skill at our disposal to try and find out what happened to the museums on this list.

For some, like the Abriachan Museum (aka the Croft Museum) in the Scottish Highlands or the Baird Museum of TV (aka the Radio Rentals Museum) in Swindon, we discovered that the museum had closed prior to 2000 and so was outside of the scope of this project.

And for others, like the Brookeborough Vintage Cycles Museum in Northern Ireland or the Naseby Battle and Farm Museum in Northamptonshire, we finally tracked down information about the closure and the dispersal of those museums’ collections. Or, as with Collectors World in Norfolk (fig.1), we had to draw inferences about the reasons for closure from a range of sources.

But we also came across other museums that complicated our ideas around closure.

These are museums, like Haulfre Stables in Llangoed in Wales, where it is not at all clear whether the museum has closed or not. To some people I spoke to, Haulfre Stables was definitely still open because the collection is still in situ. But there are no public opening hours and it was not clear how someone would actually go about arranging to view the collection. So, in this case, we made the call that Haulfre Stables had in fact closed in 2012–13 when local authority funding cuts meant that responsibility was devolved to volunteers and the site could no longer open regularly. So, despite the collection still being in situ and potentially being open if someone really wanted to see it, we are labelling this as a closed museum.

Another example are penny arcade museums where the collection is owned by an individual who may move it to different locations. With one such museum, The Olde Tyme Penny Arcade or Museum of Amusements (fig.2) that had been based at Cheshire Workshops in the 2000s, the owner still retained his collection and it was now just based at other locations. So is this a closed museum, or is it just a relocation? As the newer sites had less of a public presence as a ‘museum’ and the collection was also more dispersed amongst different sites, we again made the call that this was a closed museum, although perhaps it could be argued that it isn’t closed at all.

Sometimes we found that sections of a museum closed but other parts remained, as with Fort Perch Rock Museum on the Wirral where the building had to close for some years because of a water problem. Because of this, part of the collection, the Marine Radio Museum, closed and was removed and dispersed to other museums and collections by the Marine Radio Museum Society, but other collections focused on warplane wrecks, a local submarine loss, and the Titanic remain and are intended to reopen soon. So rather than saying that Fort Perch Rock Museum is permanently closed, it might instead be more accurate to say that the Marine Radio Museum at Fort Perch Rock has closed.

At other times, the process of closure and collection removal appeared to be drawn out and exact dates were harder to pin down. With the Doughty Museum in Grimsby, which was later renamed the Welholme Galleries and then Welholme Galleries Community Museum, the public-facing aspect of the museum seemed to end around 2004, but a freedom of information response from the council stated that the building was used as a museum store until 2009.

And then there has been the occasional museum on our list where we found that it never opened in the first place, as with Challenge at Aldershot (Military & Aerospace Museums), which was intended to open in 1995 on the army base at Aldershot but because of local authority cuts, amongst other reasons, never actually opened. So the museum can’t be said to have closed because it never actually opened.

These are just some examples of museums that have complicated our ideas around closure with it not always being as clear as one might expect about whether a museum is closed.

Helena Bonett

March 2025

Picturing Museum Data

We are currently developing visualisations of our data on the whereabouts of collections from closed museums. This is proving complex because graphs, figures, or flow diagrams are never just a simple representation of information. And that problem is compounded when the data itself is patchy and sometimes imprecise. In this post we want to discuss some of the choices we made about modelling that information.

To recap, around 525 museums in the UK have closed since 2000 and we have been investigating what happened to their collections. That information has been entered onto a spreadsheet with almost two thousand lines of information. It is nearly impossible to get a grasp on the data by simply reading it through, so we create visualisations to capture and summarise different aspects of that information. We want to better understand where objects moved from and where they have gone; the issue was how best to visually represent that information.

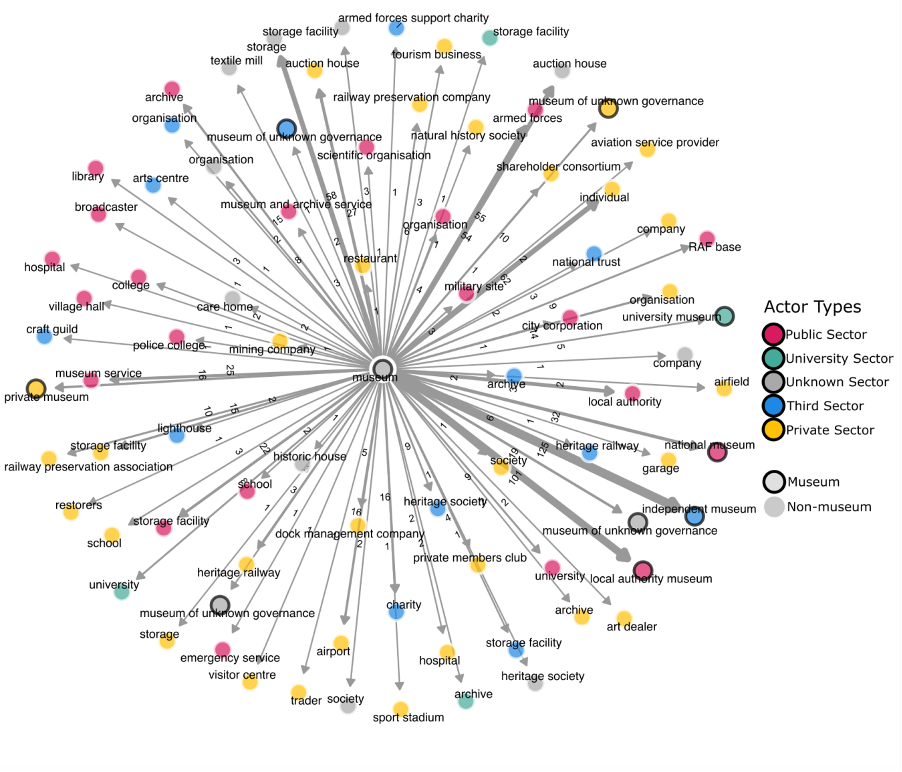

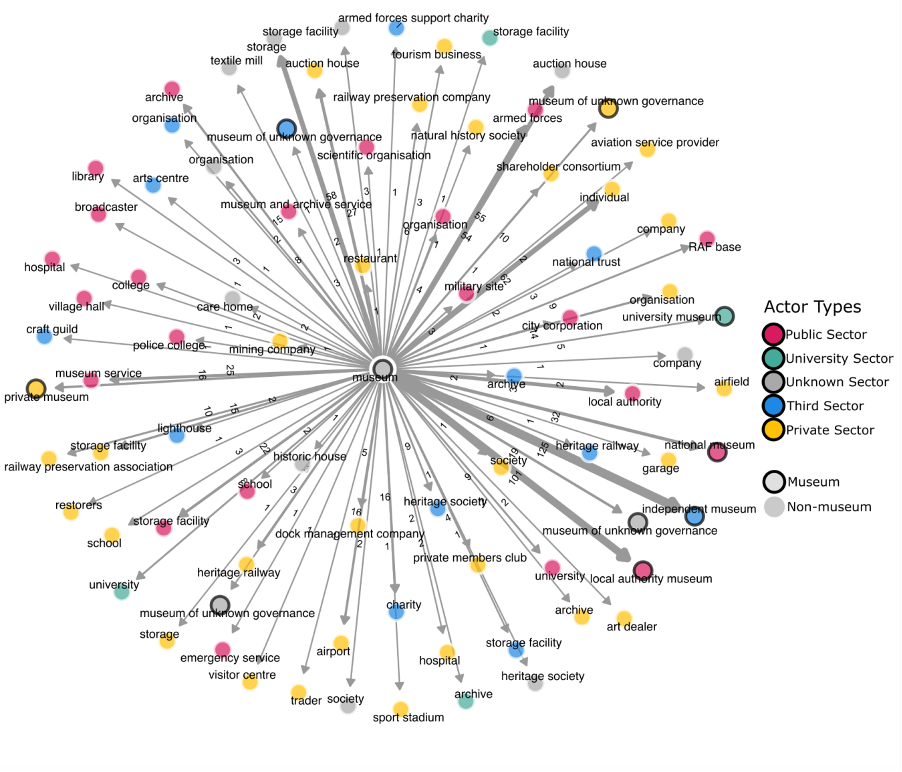

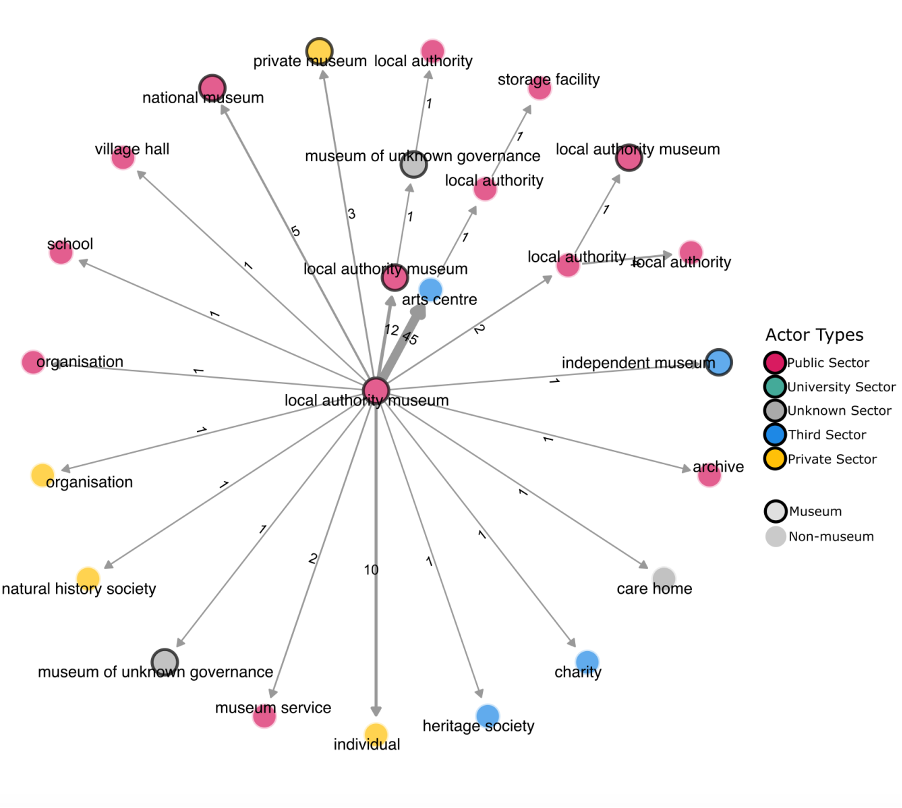

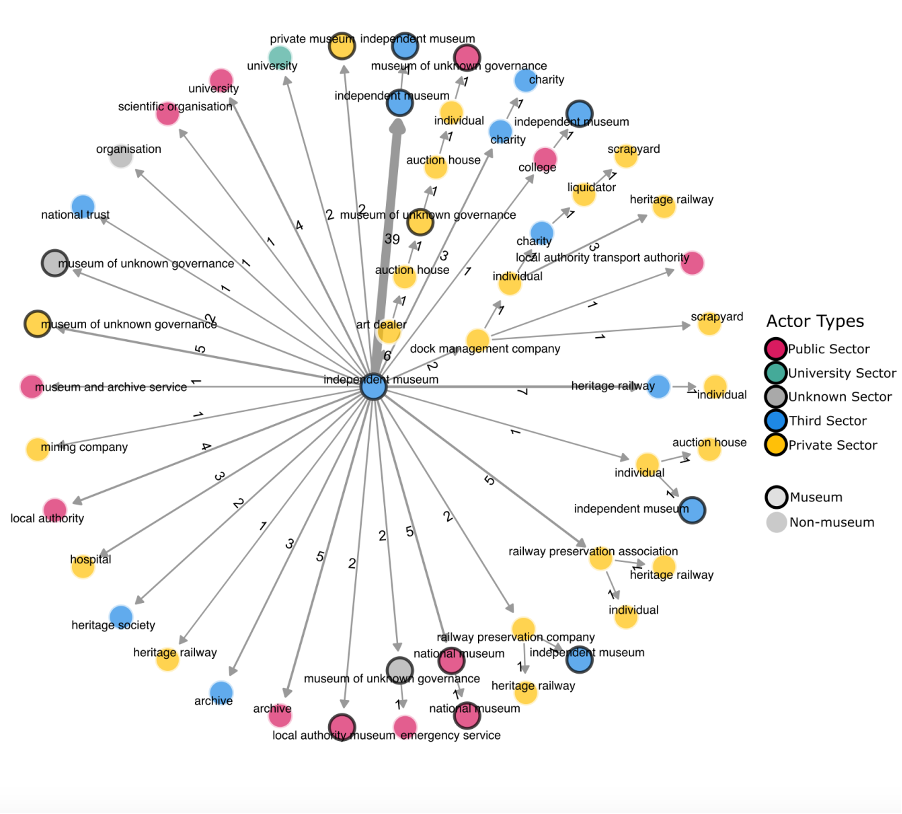

The first figure we used is known as a dendrogram (dendron means ‘tree’). The circle in the middle stands for all closed museums and the others stand for the recipients. This gave us a quick and striking indication of the sheer variety of destinations – objects moved from museums to heritage organisations, railway preservation societies, schools, mining companies, private individuals, and even airports. It was colour coded to help us differentiate between different kinds of entities: those in the public or private spheres, the third sector, and universities (which are not a neat fit with the others). We also labelled the lines or ‘edges’ with the number of transactions made, so we can see that there were sixteen transactions from closed museums to dock management companies and twenty-seven to auction houses and the lines are thicker where there were more transactions. (Please note that the data collection is not yet finished so the numbers are not yet final. Our focus here is on modelling, not the data contained within the visualisations).

This dendrogram was very general, so we filtered the data by museum characteristics, including governance, museum size, and subject matter. Figures 2 and 3 show the distribution of objects from closed local authority and independent museums, respectively. These figures also showed instances where objects had made more than one ‘jump’, for example moving from a closed museum a local authority and thence to a library or historic house.

These figures were useful because they showed the differences in the patterns of closure according to governance. We could quickly see that objects from independent museums went to a much wider range of destinations than those from local authority museums. However, we wanted to be able to make more direct comparisons: to see the museums of different types and their destinations alongside each other.

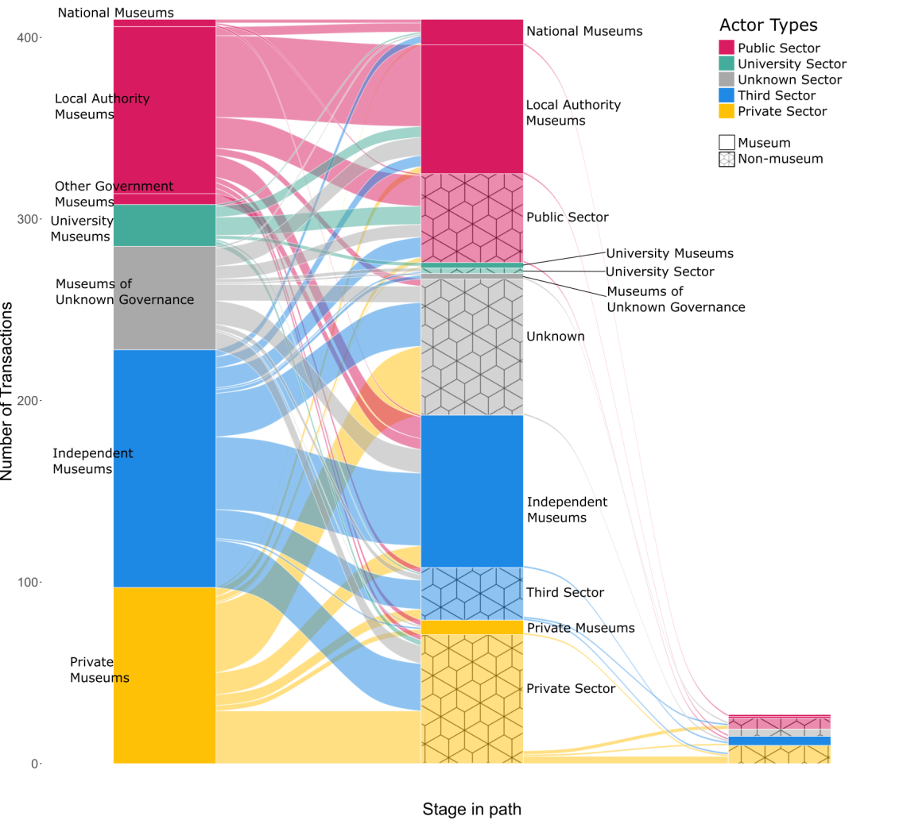

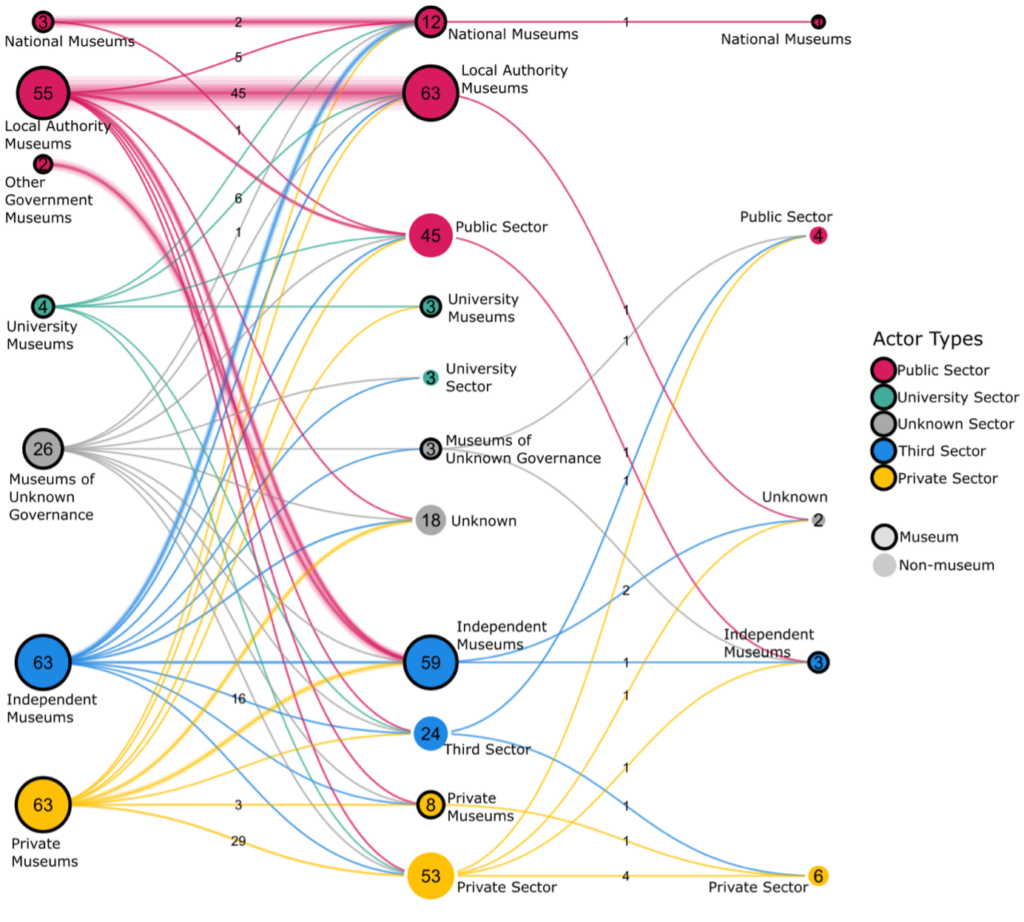

Our next step was to create alluvial diagrams, which are used to show flow and change over time. In Figure 4 the bar on the left represents the different types of closed museums, the columns on the right represent recipients, and the ribbons between them indicate the flow of objects from one to the other. The lines are coloured by source, and the actors are grouped by governance and economic sector.

So far, so good. The problem now lay in how to better represent the quantities of objects flowing out of the closed museums, and that was a much more difficult issue because it concerned the precision and detail of the available data. In some cases, we knew that a museum’s entire collection was transferred to another institution. In the spreadsheet this is logged as a single transaction: when museum X closed, all the collection went to Y. In other cases – often transport museums – we had extremely detailed information about the individual items in a collection and where they went. We wanted to capture all the information we possibly could, so each itemised transaction is included in the spreadsheet. For instance, Clarke Hall Educational Museum made transfers to sixteen recipient organisations whereas the collection from Manor House Museum was moved wholesale to the Moyse Hall Museum in Suffolk. In Figure 4 the size of the coloured blocks in the bars and the width of the ribbons relate to the number of transactions, so the sixteen transactions from Clarke Hall occupy more visual space than the single transfer from the Manor House Museum, irrespective of the size of the collections. This was an unsatisfactory solution.

To complicate matters further, some of the information we received was far less specific. It was common for stakeholders to say things like ‘some of’ the collection went to a local museum, ‘a few things’ to the town hall and ‘everything else’ went to the school. These are clearly relative measures and depend on how big the collection was in the first place. ‘Most of’ one collection may be roughly equivalent to ‘a bit’ of another. And it is rare to be able to establish the size of a collection, even when the museum is open. How then were we to model the data we had received?

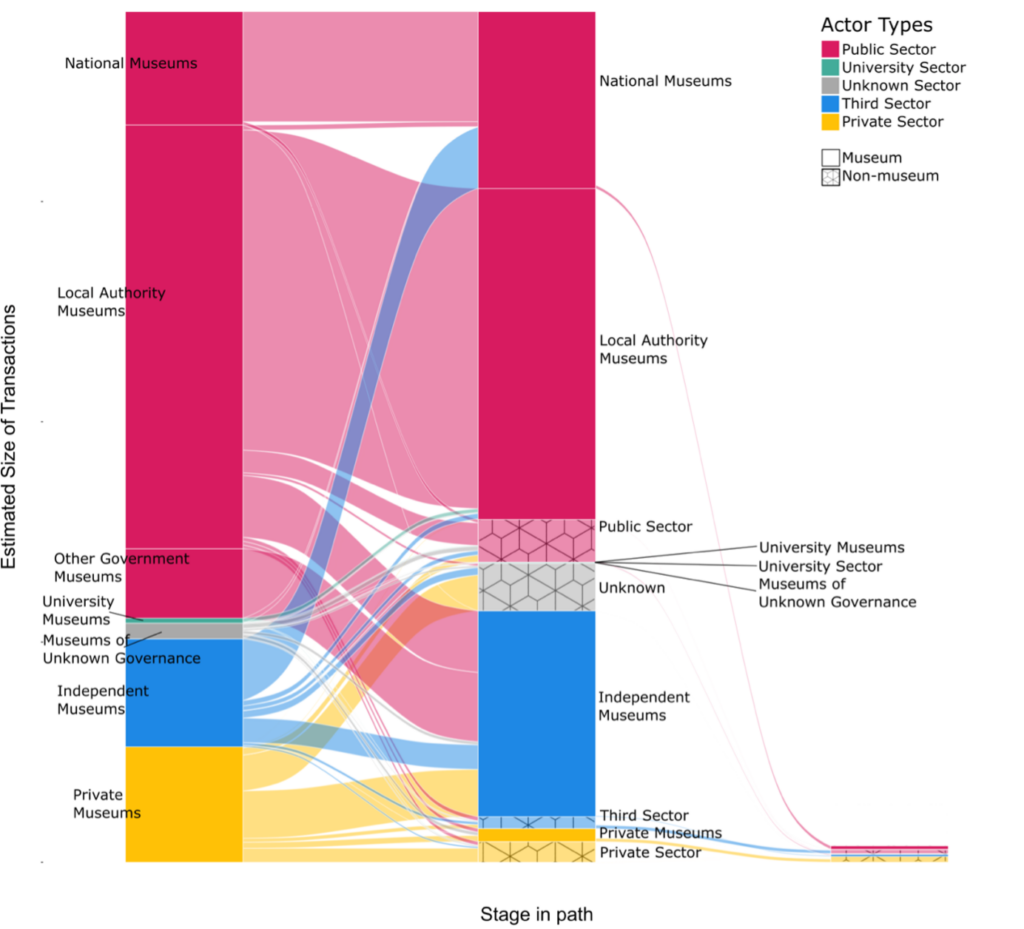

The project team devised a work-around. We estimated the relative size of transactions using the formula: (museum size x collection size), with museum size being the midpoint of the categories used in the original Mapping Museums research (small = 5,000; medium = 30,000, and large = 500,000 visitors per year) and collection size being quantified as (few = 5%; some = 25%; half = 50%; most = 80%; all = 100%). National and local authority museums tend to be larger and as you can see in Figure 5, transactions of collections starting in national or local authority museums tend to have thicker ribbons than those starting in independent museums.

Figure 5 was an improvement, but there were still problems. Firstly, the figure gave no indication of how many museums were involved in these transactions and second, there was no way to visually convey the uncertainty of the data. Third, the alluvial diagram created visual continuity between very different entities: national museums, private museums, and airports all occupied the same neatly bounded space, implying connections or similarities which did not necessarily exist.

It was time to try a different tack, so we started experimenting with network diagrams. The lines represent flows of objects between actors and move from left to right. Closed museums are represented by circles on the left, recipient organisations in the middle, and any further destinations on the right. Using a network diagram helped solve the problem of visual continuity. It also enabled us to plot the number of museums involved and the size of the transactions and to register a degree of uncertainty: the size of the circles indicates the number of museums or recipients, while the line between is both labelled with actual numbers and uses an additional band to show the estimated sizes of those transactions. Using the network diagram, it became possible to make statements such as:

‘We know of 55 local authority museums which closed during this time. We know that there were 45 transfers of ownership from closed local authority museums to other local authority museums. We think that these transfers involved a relatively large quantity of objects’.

So far this seems to provide the best solution to modelling our data, but it is still work in progress and we welcome any comments.

Fiona Candlin and George Wright

November 2024

We’ve been working on our project about museum closure for just over a year. We set out to collect information about the collections of around 500 closed museums, and our stated ambition was to cover at least 70% of them. Some of our team had prior experience of researching closed museums and knew that details were often hard to come by, so that target seemed realistic. A year on, we’ve done much better than expected. Of our initial list we have found information on over 90%.

What remains is a list of what we’re calling the stuck museums. In these cases we think we’ve exhausted our avenues of enquiry, and still don’t have information on what happened to the collections.

What have we tried? An incomplete list: Googling; meeting members of the Museums Development Network; contacting local history societies, who often had leads but sometimes knew no more than we did; asking nearby museums; consulting local authority planning documents that indicate the change of use of premises; examining auction catalogues; searching newspaper archives; for one case visiting the National Archives and for another two, the archives of British Telecom; searching social media; picking the brains of the Arts Council’s Accreditation team; using the Wayback Machine; when no contact details existed bar a postal address for directors of the small company that ran the museum, writing letters – an unusual activity in 2024; making Freedom of Information requests to local authorities when informal enquiries went unanswered; joining specialist groups on Facebook for collectors of paperweights, Matchbox cars, and antique dolls, to name just three.

That’s not all. We’ve also tried: asking members of the Subject Specialist networks; emailing the foremost writer in English on the work of a Japanese novelist; contacting organisations that used to run the museums or who now occupy the site; having obtained snippets of information, more precisely targeted Googling; interviewing specialists in regimental and transport museums; emailing local politicians, drinks manufacturers, race courses; attempting to contact a retired magician; using a website that lists the destinations of former military aircraft; seeking help from the unofficial historian of a major football club; interviewing the biographer of a man who ran two shipwreck museums; asking local libraries; reading council reports and collection development policies; asking the police (about police museums); meeting an expert on recent local authority museum closures; emailing hospitals; writing to the BBC; asking former curators, a local board of education, the National Trust, auction houses; interviewing outgoing curators.

This may sound exhaustive (and exhausting). We’ve been as thorough as we can, yet for some museums we remain stuck, with little or no information on what happened to the museums or their collections.

Can you help us with any of them? We’re looking for information on why the museums closed, what happened to their collections, and what their buildings are now used for, if they still exist.

View the list of stuck museums.

If you have any information, please contact Mark Liebenrood at m.liebenrood@bbk.ac.uk.

Mark Liebenrood

Museum Detectives

Collecting information on closed museums is a challenge. Museums usually open with a degree of fanfare but often close quietly – and their catalogues, visitor books, and other documentation are not always retained. (Although cowhide hats off to Northampton Museum and Art Gallery for keeping the data from the now-closed Museum of Leathercraft). No-one is specifically charged with keeping records from closed museums and it is hard to find anyone connected to a closed museum, especially after twenty years or more. The staff have relocated, volunteers filter off to other organisations or spend their time in other ways, people die. In this blog I’m going to outline some of the ways that we were able to collect information.

We began by scouring the internet. In some cases, websites or social media accounts lived on after the museum had closed and occasionally the final post explained the circumstances of closure and what was happening to the collections. These pages also provided contact details. Most of the time our emails bounced, and the phone numbers we called were defunct or had been reallocated to someone new, who would be utterly bemused by our enquiries, but in some cases, especially at private museums, the museum owner still lived or worked on the premises. When I called the number for Red Carriage Working Museum in Matlock, Derbyshire, the proprietor told me a moving story about being forced to close when professional burglars stole their entire collection of antique and irreplaceable harnesses, thereby making it impossible for them to show the carriages in action. Although she and her husband sold the yard and the rest of their substantial collection, they had kept the house.

In other cases, online reviews, blogs, or chat forums gave us a lead. A TripAdvisor review for the Longstone café on the Isles of Scilly, noted that it had replaced the Longstone Heritage Centre. Amy Jenkins the proprietor told me that all kinds of things had been left at the site – including two cannonballs which she gave to her father – and gave me the name of the founder who I was then able to contact. Similarly, an online chat forum mentioned that the founders of Harmonium Museum in Shipley, Yorkshire, Phil and Pam Fluke, were continuing to repair instruments. A few clicks later, I found their website and was able to get in touch. Phil also gave me some leads for other closed museums. Alternatively, we called the business at the location where a museum used to be. Jacob Clark, owner of the Animal Avenue Pet Supplies shop at Ringwood, told me that the shop fronts from the Ringwood Town and Country Experience were still outside and a collection of objects in the attic. And we put out calls for help on social media. Twitter users provided an obituary for Kathleen Mann who had run a Cat Museum at her antiques shop in Harrow-on-the-Hill in London, which enabled us to pinpoint the date of closure.

Sometimes we spent a lot of time investigating one museum to no immediate avail. Finding pictures of the Museum of Cipher Equipment in Cupar on a cipher enthusiasts’ website, I contacted the webmaster in California who emailed a call for information to his network. We also contacted staff at Scotland’s Secret Nuclear Bunker, the Museum of Cupar, and the Museum of Communications, none of whom had heard of the museum but promised to investigate further. I posted on Twitter and word spread. A historian raised it at a museums meeting in nearby Dundee and a member of Museum Association staff persuaded their in-laws who lived in the area to make enquiries on our behalf. Some months later I got an email from the owner. He had visited the Secret Nuclear Bunker and they had passed my email on to him. It turned out that the collection had been destroyed in a fire and that he had moved to Orkney.

Another alternative, especially when we were investigating Local Authority museums, was to contact a neighbouring institution. The staff were often only too aware of closures in the area and in many cases had either inherited the collection or been personally involved in its relocation. Out-of-the-blue telephone calls or emails regularly elicited extremely helpful responses along the lines of ‘The objects all came back into the service. It was before my time, but I can put you in touch with my predecessor if you want more detail. I have his email’ (Wirral Museums Service) or ‘The Lace Museum was never part of the Nottingham Service, although a lot of people thought it was. Some of the collection did come to us. I can send you the relevant section of the catalogue if that’s of interest to you’ (Andrew King, Registrar). Needless to say, it was.

Alongside our internet searches we contacted area museum services or the members of staff with responsibility for heritage in local councils. They were often extremely helpful, giving detailed information about why a museum had closed and where the collections had gone. We also met with the Museums Development Network who scanned through lists of closed museums in their regions, trying to dredge up memories of long-gone venues, as did subject specialists. Anthony Coulls, Senior Curator at the National Railway Museum in York, got in touch when he read about the research and checked our information on closed transport museums while Julian Farrance, Regimental Officer at the National Army Museum and Paul Evans, ex-Historical Projects Officer at the Army Museums Ogilby Trust, looked over our lists of closed military museums.

All of the input that we have received has been very useful: thank you to everyone who has given us information, leads, or advice. We really couldn’t do this without you. However, we’re still trying down missing information on some museums so do keep watch on this space for updates and, no doubt, calls for help.

Fiona Candlin

September 2024

Afterlives of Objects

Thursday 24th October, 6.00 – 8.00pm

Clore Lecture Theatre, Birkbeck, University of London, 25-27 Torrington Square, London WC1E 7JL

Places are free but limited and must be booked in advance

In 2009 Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins collaborated on The Object Reader (Routledge). Since then, they have individually pursued diverse research on the histories of objects, curation, design, and disposal. This conversationbrings Fiona and Raiford together again with their longstanding collaborator, interlocutor, and friend Joanne Morra to discuss their current work in progress on the afterlife of objects: Fiona is currently driving around the UK visiting closed museums for her new book on the subject, while Raiford is on a world tour of video game museums researching his next book, Museum Games: Journeys in Search of Playable Media. Both are investigating the process of collecting, exhibiting, experiencing, caring for, and scrapping objects. They share a mutual fascination with where stuff goes. Jo and Ray were Founding Principal Editors of Journal of Visual Culture (2001-2019), and previously worked together on the journal Parallax. Fiona and Jo read each other’s material.

Joanne Morra is Professor of Art and Culture and Programmes Research Director at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. She writes on contemporary art and psychoanalysis. Her publications include Inside the Freud Museums: History, Memory and Site-Responsive Art (IB Tauris 2018), Intimacy Unguarded (JVAP, co-edited with Emma Talbot, 2017). She is now working on a book provisionally titled Holding Art: Women and Radical Care.

Raiford Guins is Professor & Chair of Cinema and Media Studies in the Media School and Adjunct Professor in the Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering at Indiana University, Bloomington. He is the author of Feeling Leeds: Notes on Loving a Football Club from Afar (Pitch Publications, 2022), Atari Design: Impressions on Coin-Operated Video Game Machines (Bloomsbury, 2020), Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife (MIT 2014), and Edited Clean Version: Technology and the Culture of Control (Minnesota, 2009). Guins also co-edits MIT Press’s Game Histories book series with Henry Lowood. His newest book, Changing the Game: How Atari’s Pong Bounced Across Markets to Make Millions, is forthcoming with MIT Press in 2026.

Fiona Candlin is Professor of Museology and Director of the Mapping Museum Lab at Birkbeck, University of London. She is author of Art, Museums and Touch (Manchester University Press 2010), Micromuseology (Bloomsbury 2016), and Stories from Small Museums (Manchester University Press 2022). Her new book is provisionally titled Stories of Closed Museums.

For more information about this event contact Katy at mappingmuseums@bbk.ac.uk

The Mapping Museums Lab have been collecting data on over 450 closed museums, including what happens to their collections and buildings. As we gather information about collections, we’re learning that the data available varies widely from one museum to another. In some cases we’ve obtained a list of where every exhibit went, with the type of destination (such as a museum or private storage facility), and sometimes the state of repair of individual objects. In other cases, we have gathered little more than that the collection was sold, often at auction, and dispersed into private hands.

We’re in the relatively early stages of a two-year project, but some patterns are already starting to emerge. For instance, legal processes can have the effect of producing better public documentation for collection dispersals. Liquidators managing company insolvencies produce annual reports, which detail the disposal of assets, and a set of those reports were produced when the parent charity of the Yorkshire Waterways Museum went into liquidation. A more controversial example is the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum, where accusations of impropriety led to numerous news reports that documented the complex trajectories of some of the exhibits. Although Bristol Museums now look after the bulk of the collection, the whereabouts of some items formerly held by the BECM are still unknown.

The type of object displayed can make a big difference to the amount of information available. Museums of aviation and railways, which in the cases we’re looking at often display a fairly small number of large objects, are particularly well documented. One example is the Electric Railway Museum, which was a collection of locomotives, electric multiple units and related items, sited near Coventry. The museum’s founder kindly supplied us with a detailed list of the whereabouts of the collection, and the ownership status of each object.

The collections of closed aviation museums can also be fairly straightforward to track. Each plane, in addition to having a manufacturer and model, also has a unique identification number that enables its whereabouts to be found. I have never needed to visit the Demobbed website before starting this project, but that database of former military aircraft has proved invaluable in tracking down some of the planes that were held by now-closed museums. Demobbed features extensive lists of aircraft locations maintained by the Wolverhampton Aviation Group, who are evidently a dedicated community of enthusiasts. Each plane’s history is detailed, including whether parts of it, such as nose cones, were removed and dispersed.

Museums featuring ships and boats have also been relatively easy to track. The small collection of five ships and submarines once held by the Warship Preservation Trust in Birkenhead has been exhaustively documented. This is partly due to a museum and a heritage organisation acquiring two of the vessels. But thanks to enthusiasts keeping an eye on the others, documenting them online and sometimes campaigning for their preservation, we know that a submarine and the frigate HMS Plymouth were scrapped, while the last known destination of the minesweeper HMS Bronington was a dock in Birkenhead, where it had partially sunk at its moorings.

But for another maritime collection there is more uncertainty about destinations. The large collection of boats at the Eyemouth Maritime Centre was sold at auction in 2017. The sale attracted a fair amount of attention from boating enthusiasts, which means that we have been able to track the destinations of quite a few of the boats. However, around 100 boats were reportedly purchased by a collector and cut up to enable transportation to China. This shipment was apparently intended for a new maritime museum but we don’t know whether it ever opened, leaving the whereabouts of a substantial part of the Eyemouth collection unknown.

Although planes, trains, and ships have been easy enough to track down in many cases, car and motorcycle museums are another matter. So far, we’ve found that many of these collections go to auction and are subsequently dispersed to private buyers. Occasionally it’s possible to discover that some items have gone to museums, but not always which ones. The auctioneers of the London Motorcycle Museum told us that three of the bikes had been purchased by museums, but our enquiries have not revealed precisely where they went. The case of the Cars of the Stars museum, mentioned in a previous blog, where the collection went to just one buyer who also runs a museum, appears to be quite unusual. As the destinations of auctioned items are rarely reported, that type of museum dispersal is often the end of the trail for us.

As our research continues, it’s becoming apparent that although some collections are very well documented, sometimes down to the level of individual items, in many cases we are simply recording groups of items as moving from a closed museum. And it’s unfortunately quite likely that we will never know what has happened to many others, with the destinations of items and even whole collections left unrecorded. Those differences in what we can find out have implications for how we analyse our data. We don’t want to over-represent some collections in our analyses simply because we have more details about them, or under-represent others that are less well documented. As a team we’re continuing to discuss how best to grapple with that problem.

Mark Liebenrood

Are museums more likely to close in areas of higher deprivation? It seems an obvious question. The more deprived an area is, the less capacity the council has for raising revenue from business rates and council tax, and the more likely it is to have to cut non-statutory services, such as museums. Meanwhile independent museums in deprived areas might struggle due to the lack of disposable income. Except that turns out not to be the case.

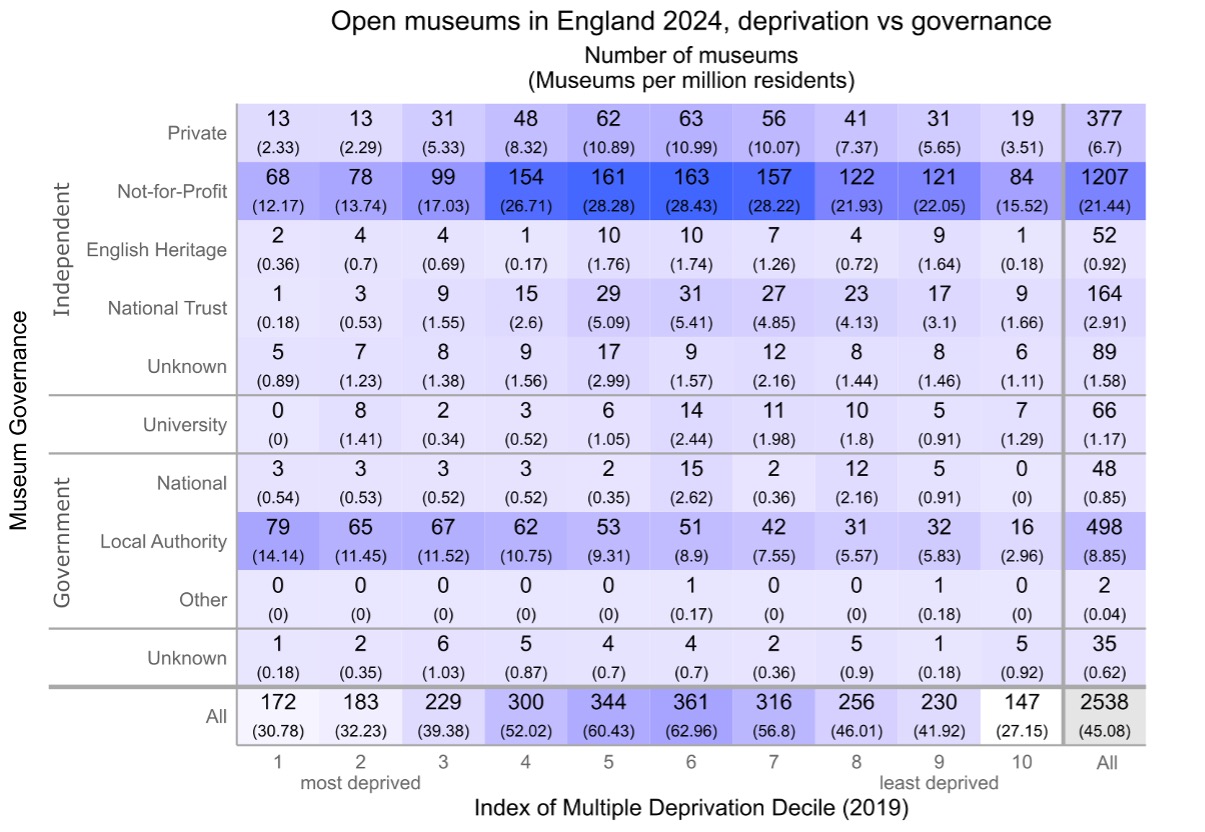

In the last blog we considered closure according to region, which provided us with an overview of museum geography in the UK. In this blog we take a more granular approach and draw on the Index of Multiple Deprivation. This is the official measure of relative deprivation in the UK and is assessed on a combination of household income, employment, education, health, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment. Using the index allows us to look at deprivation in relation to small areas with around 1,500 residents apiece, which then enables a more nuanced understanding of where museums are located and the types of places where closure occurs. Deprivation is calculated differently in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, making comparisons difficult, so in this blog we focus only on England.

Table 1 shows the distribution of open museums across England as of the beginning of 2024. They have been classified according to governance and the deprivation of the ward in which they are located. As you can see, all kinds of museums can be found in almost all areas – irrespective of deprivation. There are no national museums in the least deprived areas and no university museums in the most deprived, although both these types of museums have relatively small numbers. Most notably, private, and independent (not for profit) museums cluster in the middle ground, while local authority museums tend towards the most deprived.

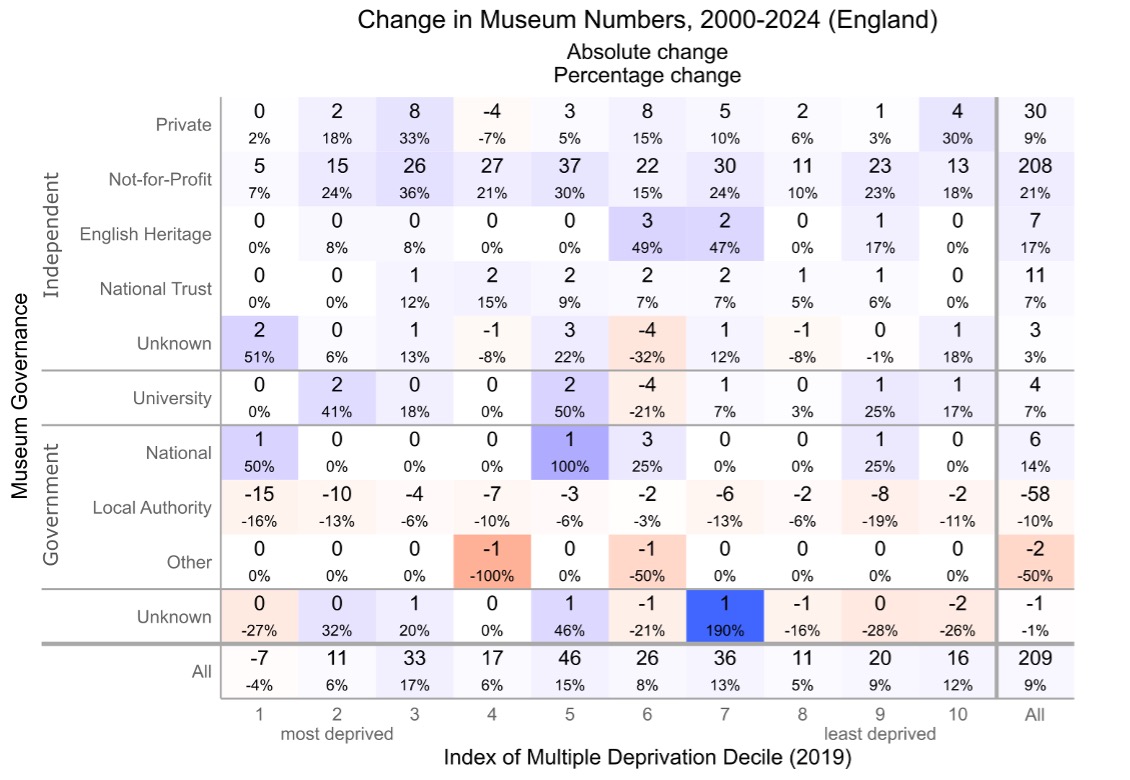

Table 2 shows change in the number of museums since 2000 and gives the percentage change in each category. As we outlined in our previous blog the number of independent (not for profit) and private museums rose since 2000. Here we can see that the expansion in numbers of not-for-profit and private museum goes across the spectrum of deprivation with large growth in the middle.

The number of Local Authority museums has decreased since 2000 but there has been less decrease in the middle ground. There has been a greater decrease in the number of Local Authority museums at the edges of the spectrum, that is in areas of most and least deprivation.

There are two important caveats to this data. Firstly, the Index of Multiple Deprivation does not equate to average affluence or poverty. Rather it looks at most and least deprived, which is slightly different. So for instance, one area may contain pockets of extreme wealth and considerable deprivation, whereas another may be less affluent but also have little deprivation in the sense that residents are all in employment, there are low rates of crime, and so on. According to the Index the first area is more deprived – there is some deprivation amid the wealth – while the second is less deprived.

The second caveat is that a museum’s location is not synonymous to the visitor catchment area. These small areas represent the immediate geographic context in which a museum is sited and visitors may come from much further afield. The degree to which they do so depends in part on the type of museum in question; whether it is a national, regional, or small local museum. Going forward we will be thinking further about calculating the distribution of museums and change according to the visitor catchment area.

Yet despite the caveats, the data shows that change in the sector does not neatly align with levels of deprivation. We cannot link museum closure to deprivation or indeed growth in numbers to a lack of deprivation.

Fiona Candlin

George Wright

Andrea Ballatore

Photo: Katy Pettit